Rails next to trails

There are approximately 212,000 at-grade railroad crossings in the U.S., usually consisting of one or more railroad tracks crossing a public highway. In some cases, and increasingly commonly, there is an additional presence of a multi-use path or trail, which adds a new level of complexity to crossings. They will often run adjacent to the railroad tracks, serving urban areas, recreational activities, light-rail station access and a variety of other purposes. In most cases they also will be crossing the public roadway close to the tracks, establishing a second point of potential conflict, as seen in Figure 1. The red X’s mark the two primary points of conflict—the conflict between the pedestrian (yellow) and the vehicle (blue), which in turn leads to the second conflict between the vehicle (blue) and the train (black), in situations where the vehicle is stopping to avoid the pedestrian.

In Oregon, as well as in many other U.S. states, it is illegal for a vehicle to stop on railroad tracks; but at the same time, it also is illegal to not stop for pedestrians, bicyclists and other users. When a non-vehicular user is present in a crosswalk and approached by a car traversing the railroad tracks, the driver of the vehicle is forced to break one of the two laws or put themselves or other road users in danger. To avoid striking the pedestrian who is crossing in the intersection, this will most frequently result in the vehicle dwelling on the tracks to wait for the pedestrian to pass. Aside from being illegal, it poses a safety threat to the driver who is in a train’s path and may not be able to move out of the way if a train, which would be unable to stop, approaches. With more complex urban intersections, with higher volumes and an increased level of information that needs to be processed by traffic participants, the probability of the occurrence of unintentional non-compliance increases, leading to conflicts between all types of users.

To adequately address the safety concern at this type of crossing, it is useful to regard these locations as a single, complex multimodal intersection. Much literature is available to guide decision-making when it comes to applying treatments to highway-railroad crossings as well as for highway-sidewalk/path crossings, but limited guidance is available regarding these complex intersections. Furthermore, these different types of users and infrastructure are represented by a variety of different stakeholders, both public and private, whose interests should all be considered. These can include the railroads, pedestrian/bike advocacy groups, cities and counties, and federal and state agencies, such as the FRA and state DOTs.

The research to address this approached the issue by identifying repeatable primary issues and constructing a framework that guides the user through assessing appropriate treatments. The goal of doing so is to improve transparency, increase efficiency in the process and to secure stakeholder buy-in, with the hope of achieving safer at-grade crossings while considering public budgets.

There are presently no general guidelines for doing this, meaning that states, counties and cities often are left to their own devices. In the best cases, it means that the responsible agency will develop its own methodology for addressing this type of intersection. In some cases, the agency will treat the location as two separate entities, possibly leading to an increase in the confusion for users and in unintentional non-compliance, as their unique influence on each other is not considered. In other cases, it may be decided to eliminate the pedestrian crossing, resulting in two unconnected trailheads on either side of a highway and with that, an increase in the occurrence of illegal pedestrian and bicycle behavior.

To assess these crossings, several methodologies were employed—first, a thorough literature review followed by in-person observations and counts, which were further corroborated by video surveillance. Finally, issues were categorized, and appropriate treatments were identified. The observations were done in Oregon, and with recommendations from the Rail Public Transit Division seven study sites of different characteristics were chosen. Detailed counts were extracted for both morning and afternoon peak times at all locations. An example of pedestrian and bike movements at a light-rail crossing can be seen in Figure 2. This figure shows a location and the observed movements at this location.

Using the knowledge gained from completing the field visits, reviewing the recorded video and the available literature, the research group identified and described three overarching causes of problems: the built environment, lack of path user information and lack of driver information. The two latter categories are concerned primarily with human behavior—our actions, skills and knowledge—whereas the first category is purely concerned with the physical infrastructure and road design, and best practices within these two areas. The built environment category can be directly impacted by engineering and planning, design, and decisions.

Figure 1. Points of conflict at road-rail crossings could include multi-use paths.

The built environment

The purpose of our transportation infrastructure is to facilitate movements that are safe and efficient. It does so through structure, such as road design, medians and sidewalks, and through information, such as signage and pavement markings. When the built environment is lacking content, such as visibility or adequate travel paths, the infrastructure is not fulfilling its purpose and safely and effectively accommodating its users. This leads to undesirable situations for everyone participating in traffic, but also for responsible engineers and planners. The primary issues regarding the built environment include too-high posted speed limits, elevated railroad tracks, difficulty for drivers assessing passage, crossing and path distances, stop lines in inappropriate locations, the presence of transit stops, inadequate visibility, and lack of grade separation.

Lack of path user information

This category is concerned with the actions and behavior exhibited by the users of the path running adjacent to the tracks, including pedestrians, bicyclists, skateboarders, and a variety of other users. The type of path that runs adjacent to railroad tracks is typically a higher speed path where the users are undisturbed by the surrounding traffic. When they do reach an intersection, it means a change in their environment, which they need to safely navigate. When users are unprepared for an upcoming crossing, they can potentially end up in dangerous situations. It is important to ensure that the path users are adequately informed of the upcoming crossing or break in their path and can be prepared to proceed safely. The identified primary issues regarding lack of path user information include too high speeds, lack of signage and non-compliance issues.

Lack of driver information

This category concerns the users of the highway who are crossing both the railroad tracks and the path crossing. While pedestrians, bicyclists and others using facilities running perpendicular to the tracks and path also are technically belonging to this category, they are not explicitly handled in this research and do not seem to pose a significant problem. As with the previous category, it is vital that drivers approaching a crossing have adequate information, knowledge and prior notification to be able to safely traverse the intersection. The primary issues regarding lack of driver information include issues negotiating the complexity of the crossing (“information overload”), vehicle speeds, and lack of signage or too much signage confusing the driver.

The three categories with their 14 subcategories described in the full report together describe the primary issues and an overall picture of potential conflicts at a complex intersection. These mechanisms should all be considered when attempting to remediate undesired situations or behavior at an at-grade multimodal crossing.

Addressing primary issues

The developed methodology is directed towards agencies attempting to select cost-effective treatments, which addresses primary issues at complex intersections. It assumes that the crossing in question is of concern to public safety. For this purpose, it also assumes that the responsible agency has information about the crossing and/or a methodology for collecting such. The primary issues are then decided based on existing knowledge and categorized according to the three primary categories and their subcategories presented in the previous section. Types of information relevant to assessing the intersections include whether the location is heavy or light rail, as well as:

- Identified Issues: These are identified at the agency’s discretion from existing or newly collected data, e.g., number of trains per day, nearby activities, recent incidents or AADT, field visits, video recordings or other sources; and

- School Locations: Typically, traffic engineers and planners are especially concerned when a location has young children. Studies found that children under the age of eight were involved in “excessive gate-related violations in the absence of older crossing users.” For this reason, recommendations are different and the treatments generally more severe when the crossing is located within 0.5 miles of an elementary or middle school (K-8).

Figure 2. An example of pedestrian and bicycle movements at a rail crossing.

Applying the methodology

Using the process outlined above enables the user to identify the primary issues and a selection of appropriate solutions, using the individual prescriptive tables. As the issues and/or parameters of a crossing increase and change, so do the suggested solutions at the agency’s discretion.

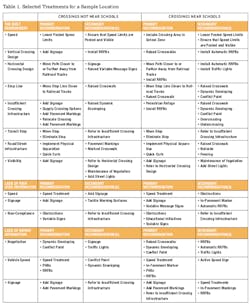

The issues are selected based on a combination of field observations, video surveillance, public comments, previous history of incidents and engineering judgment. Once the primary issues are identified, the characteristics of the crossings described and the appropriate solutions are selected and sketched. An example of the selection of treatments is given in Table 1.

After the appropriate treatments are selected, budget should be considered, stakeholders involved and plans for implementation made. These items are all detailed in the guidebook and its accompanying documentation but are, for the sake of brevity, not described in this document.

The proposed methodology is designed to be able to balance a predetermined, prescriptive approach with the professional judgment of the agency carrying out the investigation. It allows the practitioner to utilize collected information about a complex multi-modal intersection, apply it to a predetermined set of specifications using engineering judgment and by that coming up with a set of treatments that has previously been found to address the issues identified. A previously agreed upon methodology allows the relevant agency to streamline its crossing improvement efforts; to easily communicate and inform the public of the decisions made and their reasons for doing so; to secure stakeholder buy-in prior to starting a project or investigation, which will in turn lead to better outcomes; to make sure that approach and selected treatments are more standardized; and ensure transparency in the organization to make at-grade crossings safer for pedestrians and bicyclists, without negatively impacting trains or vehicles.

The authors would like to recognize Manali Seth, Edward McCormack and Polina Butrina, who contributed to this research.