Riding the A Line

Sometimes, taking the bus in a busy system in a busy area can be a gamble.

As a rider, you know that the bus is coming eventually, but traffic can impact how quickly it gets to you. Buses need to stop safely, pick up passengers and collect fares, and then get back into traffic, leading to speed and reliability challenges. And during a Midwest winter, every minute spent shivering near a pile of snow can feel like 20.

The largest transit provider in the Twin Cities area, Metro Transit, is betting on arterial bus rapid transit (BRT) to provide faster service and improved facilities for transit riders. Known elsewhere as Rapid Bus or “BRT Lite,” arterial BRT aims to provide premium, light-rail-quality service in constrained urban environments without a separate guideway. Today, the region’s first arterial BRT line is under construction and poised for 2016 operations, the result of several years of development and problem solving.

Doing the research

Since the 2000s, Metro Transit and its partners have been improving Twin Cities transit service in a big way. Two constructed light rail transit (LRT) lines and a highway BRT line connect the region’s population and jobs centers, with several more lines in design or under environmental review. High ridership proves that residents and commuters are enjoying the perks of this system, and station areas are becoming hubs of development as the system matures.

A crane postions a shelter into place, which will eventually feature on-demand heating and integrated lighting.

But the high cost and expansive footprint of LRT doesn’t fit every corridor, especially built-up parts of the central cities. To expand premium transit service to these areas, Metro Transit explored creative ways to fit the features of light rail into a smaller, bus-based package. In 2011, Metro Transit began studying how to improve speed and customer experience on a dozen of its highest-ridership bus routes. These routes carry 90,000 daily riders—or about one-third of Metro Transit’s bus ridership—and ridership continues

to grow.

Current bus operations on these workhorse routes face two main issues: slow speeds and inadequate facilities. Service speeds are hampered by red-light delays and long stops as customers pay one by one. Because traditional roadway design has prioritized getting buses out of traffic and into bus bays, sidewalks are pinched at bus stops—where pedestrian activity is highest. As a result, curbside facilities don’t reflect transit’s role as major people-movers, with many marked only by a pole in the ground. Where sidewalks are wide enough for bus shelters, shelters fit the streetscape awkwardly, leaving little room for pedestrians. These challenges persist despite transit’s major role in moving people: In a typical high-volume bus corridor, buses make up less than 3% of vehicle traffic, but carry up to one-third of people traveling.

Arterial BRT emerged as a solution for these challenges. Among the dozen routes targeted for enhancement, Snelling Avenue arose as a high priority for strengthened bus service. Metro Transit’s study prioritized Snelling for implementation of the first arterial BRT line—dubbed the A Line—largely based on its connections to the METRO Green and Blue LRT lines. Local partners wanted to see this move forward, and potential funding through the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) and other grant sources was on the horizon. All the pieces were falling into place—Metro Transit just needed to figure out how to address the corridor’s challenges with a transit system sized to fit the corridor.

Reinventing the wheel

The A Line would address these challenges through a comprehensive package of improvements. Since a major way to minimize delay is to make fewer stops, A Line stations would be spaced approximately every 1⁄2 mile, instead of every 1⁄8 mile like traditional bus stops. Payment would be taken fully off-board—riders would pay fares at the station before boarding the bus. That way, when the bus pulled up, passengers could board quickly through every door, eliminating front-door queuing and drastically reducing the amount of stoppage time.

Shortening the station dwell time allowed Metro Transit to reposition bus stops relative to the travel lanes—without wreaking havoc on traffic. Instead of pulling the bus to the side of the road, pinching pedestrian space, A Line buses could stop in the travel lane. Curbs would extend into the current parking lane to provide more space for a station platform and pedestrian throughway.

Stations would provide all the same features as light-rail stations, including:

• Substantial shelters with push-button heat and better lighting;

• Better maps and information;

• A real-time bus arrival screen;

• Security cameras and emergency telephones; and

• Ticket machines.

The result would be a fast and frequent service that gets people where they need to go and provides comfortable stations for waiting.

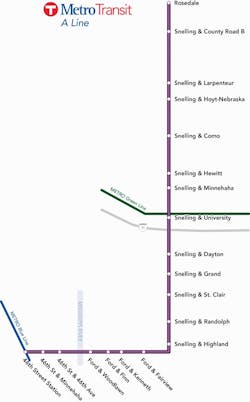

A station map of the Metro Transit A Line.

Working together to make it work

With a sound premise in hand, Metro Transit’s newly formed BRT Project Office was ready to advance engineering on the A Line. Since this project was entirely new for Metro Transit and the Twin Cities region, Metro Transit looked for a partner with experience and lessons learned from transit projects in other areas. In early 2013, Kimley-Horn was brought on to support the engineering phase, bringing ideas from similar projects across the country.

“Collaboration was key,” Metro Transit project manager Katie Roth stated. “It took a lot of back and forth to turn our vision into reality. We’d devise a potential solution, tweak it, get feedback, come back to the drawing board and then start that process all over again on the next challenge.” As the design team worked on the project, they realized just how interconnected the pieces were—all the features of the design tended to impact other features.

The team faced two main design challenges: site-specific constraints and overarching architecture and systems requirements that impacted the size of the stations. The team had to figure out the overall functional and visual elements of the arterial BRT system from scratch—developing iconic architecture, designing functional systems and figuring out how all the different technological elements would fit together. These system-wide pieces were then layered onto each of the 38 station platform sites on the A Line.

From the start of the project, Metro Transit knew it wanted a distinctive look for A Line stations to strongly communicate to customers that the A Line was not the bus they were used to. An early concept called for an iconic “pylon” marker to be erected at each station, easily seen from a distance.

The initial concept presented a lighted pylon that would bear the Metro Transit logo and contain all the necessary equipment to power the station equipment—including a real-time sign, a security camera and an emergency telephone. As the team determined what needed to fit in the pylon, the pylon ended up being much larger than anyone imagined—a hulking 2-by-3-ft base, stretching 16 ft into the air to accommodate all of the equipment. Working together, the design team eliminated and relocated some equipment, and slimmed down other elements to get to the final design. Metro Transit and the design team dismantled and then rebuilt the original vision to find something that worked from a communications, architectural and structural standpoint, and met the needs of internal and external stakeholders.

The design team didn’t stop there. The “beacon”—the top part of the pylon—is designed to be backlit. The LED lights in the pylon cap are tied to a control that connects with the GPS on each bus. When a bus approaches the station, the beacon will pulse to alert riders that the bus is approaching.

A crane postions a shelter into place, which will eventually feature on-demand heating and integrated lighting.

The pylon design, with its complementary shelter architecture, helped define what the stations would look like and impacted how elements could fit within the space. Simultaneous development of site plans and station requirements challenged the design team. To further complicate the issue, station designs had to work for each of the 38 sites on the A Line, and also serve as the template for all stations in the fully built-out arterial BRT system—envisioned to one day consist of more than 400 stations. The stations also were intended to be modular—the whole design is a kit of parts that can be expanded and right-sized to each station site.

Another key design consideration was the platform curb height. Curb heights vary by station, but the target curb height is 9 in. Metro Transit was aiming for a “near level” boarding condition—not exactly roll-on, roll-off, which can’t really work in a mixed-traffic environment or be done in a way that the buses can still move rapidly. This 9-in. curb design lets buses move at a normal speed and works for any of the buses in the fleet (not just one make or model).

This diagram depicts the upgraded features of each Metro Transit bus station.

Continuing the culture of collaboration

It wasn’t just internal collaboration that could impact this project’s success—the A Line runs on a state trunk highway and two county roads, and passes through four cities. Metro Transit and the design team worked with MnDOT, Hennepin County, the city of St. Paul and Ramsey County to coordinate design activities with planned roadway streetscape and reconstruction projects. “We didn’t want the A Line to be yet another construction headache for area residents and business owners,” Roth explained. “We were incredibly fortunate that our partners were able to align projects with our station plans, to bring several visions to fruition in a single construction season.”

MnDOT even advanced a planned bridge and street project on Snelling Avenue by several years into the 2015 construction program, allowing for A Line stations to be constructed seamlessly with its project and priming the finished A Line to operate uninterrupted by future construction.

The collaborative attitude for this project continued through plan development and agency review. Metro Transit needed to facilitate plan review with MnDOT, two counties, four cities, and three watershed districts. In many ways, the A Line plans were unlike any road reconstruction plan set these agencies had seen before, so Metro Transit started by sharing with each agency how this project would be different. “Making sure that everyone had an understanding upfront helped smooth the process,” Roth said.

The public also had opportunities to put their stamp on the project. In addition to outreach around station locations, Metro Transit solicited direct input on station design through outreach and social media, receiving over 1,100 survey responses and directing the preferred design for shelters. Community members have expressed excitement about this different kind of bus service.

Ready to ride . . . almost

Today, the A Line is in construction and scheduled to open to riders in 2016. Roth expressed Metro Transit’s excitement for the project: “We’re hopeful that successfully launching the A Line can build excitement around arterial BRT’s potential and help us get closer to connecting the region with high-quality transit service.” During A Line development, residents and commuters didn’t really know what to expect—what the A Line would look like, how it would work or how it would differ from existing bus service. Having an operational line that meets the needs of the public and performs well is critical to moving the arterial BRT system forward in the Twin Cities.

As they work toward a successful launch of the A Line in 2016, Metro Transit is preparing for build-out of a regional system, starting with the next line on Penn Avenue North in Minneapolis. Roth offers the following advice to designing and implementing a successful arterial BRT line:

• Consider the needs for transit in your corridor and your region, then right-size the design solutions to those needs. Every aspect of the A Line project was predicated on identifying a problem, and then coming up with the tools to solve it;

• Set a clear vision of what you want to achieve. After Metro Transit had an end goal in mind, it was just a matter of getting from that vision to the nuts and bolts on the ground; and

• Coordinate and collaborate. Work with your partners to determine who builds what, and you’ll more than likely minimize costs and impacts for all stakeholders. TM&E

Roth is project manager, BRT/Small Starts, for Metro Transit. Rasmussen is an engineer with Kimley-Horn.