A “Ray” of light amidst gathering clouds

The topic of sustainability often prompts the question of who is responsible for leading such efforts in road and highway development.

While many constituents recognize the need to introduce a greater focus on long-term environmental and climate issues, the responsibility for this introduction often remains unclear. Are long-term adaptation or mitigation issues the responsibility of the owner, or is it a professional responsibility of the engineer to bring these issues forward?

Recent requests for proposal (RFPs) and projects by entities as diverse as the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), the city of Sarasota, Fla., and the 100 Resilient Cities Foundation are only a sampling of what is now placing a new focus on this topic. Additionally, federal initiatives including the Executive Order—Preparing the United States for the Impacts of Climate Change issued in 2013, which focused federal agencies on developing climate action plans, and FHWA Order 5520 issued in 2014, which established the Federal Highway Administration policy on climate-change preparedness, have placed a new emphasis on agencies to take proactive action on climate resiliency.

A separate approach to addressing sustainability in highway and road projects is being adopted by the Ray C. Anderson Foundation in Georgia. Established in honor of the late Ray Anderson, founder of carpeting manufacturer Interface Inc., the foundation is focused on advancing knowledge and innovation around environmental stewardship and sustainability. This broad focus has been applied to the road and highway sector in the form of “The Ray,” a 16-mile segment of I-85 in Troup County, Ga. The goal of The Ray project is to create a proving ground for the evolving ideas and technologies that will transform the transportation infrastructure of the future. The foundation is focused on creating one of the first sustainable stretches of highway in the world, which can then serve as a model for the future of highway development. This focus includes a broad set of objectives that will establish The Ray as a leader in incorporating innovations in the areas of wildlife conservation, climate modeling, renewable construction materials, efficient lighting and signage, as well as improvements in vehicle safety and efficiency. The ultimate goal is a highway that will be zero-carbon, zero-death, zero-waste and zero-impact.

This broad set of objectives incorporates an equally broad set of innovative initiatives being pursued by a global team of traditional and nontraditional highway constituents. A key project initiative is the anticipatory incorporation of future climate impacts in the design of The Ray. Focusing on both traditional design approaches as well as project innovations, this effort is demonstrating the potential economic and environmental impacts of climate change on The Ray and the Troup County community it serves.

Climate impact initiative

The focus of the climate impact initiative within The Ray project is to quantitatively evaluate the potential impact of climate change on the existing stretch of highway as well as on future innovations being considered for implementation. In this effort, the Infrastructure Planning Support System (IPSS) by Resilient Analytics is being used to provide the quantitative analysis required to objectively determine the potential impacts of climate change as well as the potential benefits of proactively adapting to these changes with alterations in design and materials.

The basis of the analysis lies in the material and engineering knowledge captured in the IPSS system as well as future climate projections. The design and maintenance of highways is based on the historic assumption that future climate events will follow historic patterns. However, as climate modeling and actual events are demonstrating, this assumption is likely to be incorrect. The future climate in which infrastructure operates is anticipated to change dramatically over the projected lifespan of the infrastructure element. Factors including temperature, precipitation, flooding and wind are all projected to experience changes in the upcoming decades.

IPSS analysis provides a range of potential climate scenarios that may impact The Ray as well as surrounding areas. These results are based on a combination of climate projections, material properties, and accepted highway design guidelines. In this approach, climate models approved by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) are used to obtain future projections of temperature and precipitation. These projections are subsequently compared to historic weather data from local weather stations over the last 50 years. This historic data is the basis for design guidelines in areas as diverse as culvert design and bridge seal considerations. The future data obtained from the IPCC models has been compared to historic data to determine both the degree of change as well as the timeline for the projected change. In cases where the climate changes are significant enough to warrant design modifications or to predict potential increases in maintenance requirements, economic costs are calculated based on local conditions for maintenance and construction costs. In this manner, the incremental cost of climate change is calculated for each of the climate models in the study. In the case of The Ray, 40 of these models were available for the Troup County area.

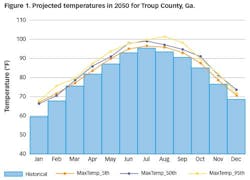

An example of the future climate variance associated with these models is highlighted in Figure 1, which summarizes the temperature data for Troup County in 2050, including the historic levels and the lower-, middle- and higher-end climate projections. As illustrated, each percentile shows an increase over historic temperature levels. A similar set of projections exists for precipitation and subsequent runoff and flood recurrence intervals. These sets of projections provide the alternative conditions under which The Ray could be expected to operate. The challenge for the design team and the Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) alike is what future should be considered as the basis for the design and investment decisions for The Ray.

Climate analysis

The generated climate projections provided a basis for determining the vulnerability of the Troup County area to future climate events and conditions. As illustrated by the temperature results, future changes are anticipated at all levels of climate projections. Putting this concern in specific perspective, the Troup County area experienced heavy flooding during 2015 that resulted in over $1.25 million in damage to local roads. In contrast to traditional records indicating that such an event is a rare occurrence that may not be seen again for decades, the projected changes in precipitation and flood levels makes this occurrence a potentially more frequent reality.

The financial impact of this vulnerability was calculated in terms of the existing highway design and the projected maintenance that was scheduled for the I-85 corridor. Additionally, since the economic impact of the highway is not limited to the functioning of the highway itself, a broader perspective also was adopted for the analysis, in order to incorporate feeder roads.

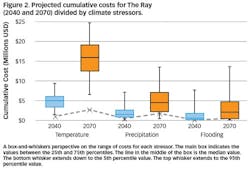

Figure 2 illustrates one component of these results, the cumulative vulnerability costs for The Ray at both the 2040 and 2070 timeframes. As illustrated, the costs are divided into the impacts anticipated by the three primary climate stressors: temperature, precipitation and flooding. The variance in cost projection changes with each stressor and with the timeframe. In each case, temperature is the primary driver of increased costs to the project as a result of the increased maintenance that is anticipated because of the weakening of the asphalt surface and associated increases in cracking and maintenance costs. By 2040, these costs have a non-discounted, median value of $5 million, while these same costs are projected to increase to $17 million by 2070.

The variance in these costs increases subsequently in the analysis. Both the potential costs and the variance in the cost increases. This is due to variance in the projections that occur between climate models as the timeline increases.

However, the overall message remains consistent with both timelines. In each case, temperature remains the primary concern with precipitation impacts following and flooding impacts having the smallest potential incremental costs. However, taking the median costs of the three stressors, the potential vulnerability at 2040 is approximately $8 million, which grows to $23 million by 2070. Given that the highway is only 18 miles in length, this is over $1 million in additional costs that can be anticipated because of projected climate changes.

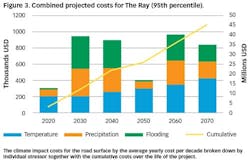

Figure 3 illustrates this cost from the perspective of decadal averages as well as by stressor for a higher-level climate projection (95th percentile). As illustrated, the average yearly cost changes over time based on the impact of the different stressors, with the variance in flooding impacts being the primary variant. However, the results also indicate that climate impact is not something that is a distant concern. Rather, climate impacts caused by temperature and precipitation increases will be seen in ten years or less.

Climate implications

The vulnerability results for the existing I-85 section that is to become The Ray provide an indicator of the level of impact that climate change may have on the highway. The option for the project directors is whether to accept those potential increases as the cost of operations, or to invest in alternative designs or materials that may mitigate these expenses by proactively adapting to the changing environmental conditions. In the case of The Ray, the decision has been made to proactively adapt where economically and environmentally feasible. Staying true to the vision of creating a highway that is a model for future roads and highways, the Foundation is actively investigating both established and emerging technologies as mitigating approaches for the projected effects of climate change.

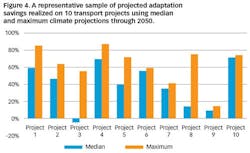

The advantage of this approach can be seen through results that have been modeled previously for entities focused on mitigating the potential impacts of climate change. As seen in Figure 4, representative projects from multiple global locations show a projected savings from adaptation in nine of the 10 projects for both the median and maximum climate projections. In the one project that did not show savings, the projected loss was limited to 5% and was restricted to the median climate projection. The average savings across all of the projects for the median and maximum projections was 40% and 63%, respectively.

The implication of the results obtained from previous projects together with the effort being put forward for The Ray is that new decision points are emerging for highway and road projects. The traditional perspective of designing to historical norms is no longer relevant according to the climate models. These changes have tangible impacts on projects. Increased degradation of pavements, weakening of bridge piers and culvert failures are only a few of the potential impacts to roads and highways that can occur from changes in environmental conditions. Given this potential impact, the question returns to the original challenge posed at the beginning of this article: Who has the responsibility to address these potential impacts? Do owners have a fiduciary responsibility to the public to evaluate the risks associated with climate change? This is the implicit message being put forward by rating systems such as Envision that include climate-change impact consideration as a component of the infrastructure rating system. However, it is equally reasonable to assert that engineering firms have a professional responsibility to incorporate climate considerations during the design process. This perspective incorporates multiple challenges from legal liability to the role of building codes and standards in terms of professional responsibility.

The ultimate answer to these questions will likely settle somewhere in the middle. However, the influence on that result is emerging today through projects such as The Ray. Owners and designers that are taking a proactive approach to addressing the emerging issue of climate change are placing themselves in a position to set a new standard for professional and public responsibility toward the inevitably changing environment, in order to create the next generation of climate-resilient highways.