What the weather is like

There’s a 100% chance that the weather will change. The best tool road crews have to get out ahead of that changing weather is time. Having to “chase a storm” is costly and dangerous. Nobody’s happy: citizens, government officials, schools, businesses and least of all, the snow fighters who may feel that they’ve been let down by supervisors who’ve made an already challenging job nearly impossible.

That’s why the real purpose of accurate weather forecasts is to buy crew leaders time to evaluate their options and make strategic internal decisions. Bringing crews in early before rush hour or keeping them late for a snow that will start sticking shortly after their shift should end, having trucks loaded and ready to roll, communicating early amongst other affected departments such as fire, police and public relations are just some of the important benefits to be gained by taking the guesswork out of weather forecasting.

In recent months, the city of Ellisville, Mo., Public Works Department got a severe warning text alert at 1:15 p.m. followed by a more specific warning phone call at 2:15 p.m. Their private meteorologist explained that thunderstorm winds arriving for the afternoon commute would definitely bring trees down. Ellisville kept crews late. The storm, which took out power to over 150,000 utility customers, hit 15 minutes after the time crews would have been heading home. As soon as the storm quit, trucks rolled. Storm cleanup was underway. Local businesses and residents really appreciated the immediate storm response. Making city leaders happy was another bonus. That day, unusually, the National Weather Service (NWS) experienced a communications outage throughout the country. Digital delivery of many warnings was delayed until after the severe storm had passed. Had the city of Ellisville not been alerted, crews would have been driving home through dangerous weather, their street superintendents would have been struggling to call workers back in and when they reached them, crews would have had to dodge falling debris on the roads while driving back to work. Logistically speaking, lead time for changing conditions that will affect a changing strategy should always be the primary goal of analyzing weather.

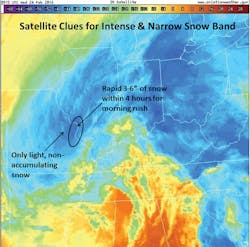

Understanding how to evaluate all bands of satellite imagery is crucial to effective planning.

Playing meteorologist

There are highly valuable benefits to having a professional meteorologist’s input when making snow and ice decisions. However, the fact is that the Internet and apps have made most people believe that they’re the weather expert. Today, if someone asks what the weather will do, everybody within earshot will reach for their device, bring it up with a fast crook of their elbow and smack their finger opening their favorite app.

Between that and the plethora of turnkey business weather applications that can be integrated into operations centers, the “don’t try this at home” warning from professionals falls on deaf ears. Many road weather supervisors work hard at matching their actions to trends they spot in weather data. Let’s expand that knowledge base by taking a look at some best practices that can help improve winter road maintenance decisions.

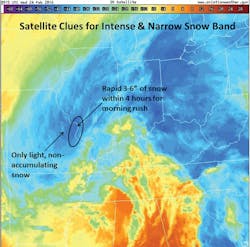

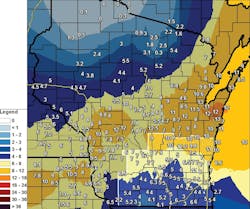

St. Louis area snowfall totals on Feb. 24, 2016.

Narrow band, wide implications

The view from above is often overlooked as a weather forecasting advantage. Satellite imagery has never gained the broad appeal of the ever-colorful radar tools. Since you cannot get rain, sleet or snow without a cloud, learning to interpret satellite products should be part of every seasonal weather procedures review. You do review weather forecasting procedures before every impactful season, right? We’ll get there later.

For now, let’s concentrate on the strategic advantages satellite data can provide from both a geographic and lead-time perspective. On a macro scale, viewing the big picture as storms set up, intensify or begin to fall apart can offer several hours’ notice before so much as a flake flies.

The best satellite products for winter weather threats are derived from the infrared (IR) band of the radiation spectrum. IR images indicate moisture in the mid and upper levels of the atmosphere. While that alone will never tell you exactly what is happening on the ground, the clues can be advantageous for snow bosses, especially when a narrow band of snow is likely. Narrow bands commonly have steep snow gradients. That is exactly what happened in the Midwest last winter.

With air temps near 40° and roads at 32-34°, the most convincing evidence that heavy, wet snow would fall so intensely that it would cool roads and bridges enough to accumulate quickly and wreak havoc for rush hour was to be found on satellite imagery. With an afternoon forecast of sun and warmth, road and air temps would rise to 44°, bringing in a full snow crew may not have been considered by all snow bosses. After all, by afternoon, both air and road temps would rise again to 44°.

Snow was already in the prior evening’s forecast. With only a narrow band of snow being expected, some may have only had a skeleton crew scheduled and some may have thought they would just chance it. After all, “a narrow snow band” can sound quite iffy as to how it will actually impact an individual city.

Monitoring satellite images in the wee hours of Feb. 24, 2016, the trained eye was looking to see where clouds would rise tall enough and expand deep enough to hint where snow would fall. The IR satellite showed precisely where the narrow band was setting up. This intensification not only showed that the rain/snow mix would change to all snow but that it would be very heavy snow with rates up to 1.5 in. per hour.

The IR satellite imagery measures the temperature of the cloud top. The cooler, or in this case, bluer the clouds, the taller they are. Hence colder cloud tops. Temperature decreases as altitude increases. Think about climbing a mountain. The higher the elevation, the colder it is at the top. It also suggests that clouds will be deep enough for snow, which is your first clue that hours before the heavy wet snow would challenge road crews, the “iffy, narrow snow band” had St. Louis’ and surrounding communities’ name on it. Radar, road weather information systems (RWIS) and surface data would eventually support what the satellite image hinted at. The key takeaway here is that the satellite data gave the early warning sign that if snow crews didn’t move immediately, the morning commute would be gridlocked.

The steep gradient of this narrow snow band, from 0-6.5 in. within roughly 30 miles, is seen here in a post-storm report. In some cases, just a few miles separated the 0.4 in. of snow which was manageable with materials alone vs. 6.5 in. of snow which required plows for safe travel during rush hour.

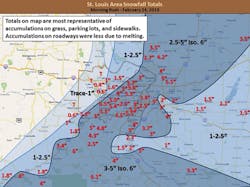

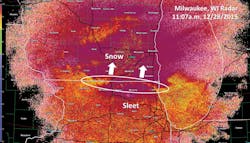

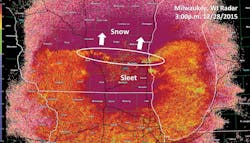

A transition line could be seen south of Milwaukee as early as 11 a.m. (top image; white circle). Snow began changing to sleet in Milwaukee around 3:50 p.m. The radar image at 4 p.m. indicates the transition line (bottom image; white circle).

Maybe turns to definitely

For the state DOT, this technique would have answered questions such as on which counties should we concentrate our resources for rush hour? St. Louis, St. Charles and Jefferson counties could have seen the same. Within the metro area, it would have been too challenging to know exactly which city would get the highest amounts. However, knowing two hours ahead that 1) there would be heavy snow for rush hour, and 2) it was setting up very close to the metro area is critical information for decision support leaders.

A time-elapsed loop shows that by 2:30 a.m. the “maybe we’ll get snow” became an “it’s definitely us” forecast so “get moving now.” The heaviest snow fell between 4 a.m. and 7 a.m. Another reason to pull the trigger on calling in crews was that heavy snow would overcome the pavement temperatures, causing snow to pile up quickly. This information was a great complement to RWIS, which did lower to near or just below freezing during this event in the morning.

Up, down and across

A significant advancement to weather radar in recent years is dual polarization, commonly known as dual-pol radar. Before this, weather radars only transmitted data from a horizontal beam. Dual pol retrieves data from both horizontal and vertical readings. This can be quite helpful during a mixed winter precipitation event. The real clue it offers to decision makers is where and when to expect the transition of whatever precipitation types are in the forecast.

Chicagoans likely remember last December when they got pummeled with a record-breaking 1.9 in. of sleet officially recorded. Just to their north, the storm put down several inches of snow in Milwaukee before transitioning to sleet around 2 p.m. The sleet continued for several hours thereafter. Using the dual-pol radar, the transition line (from sleet to snow) could clearly be seen on the Milwaukee radar.

That is the real benefit of dual pol: Seeing the transition line. The Correlation Coefficient aspect of radar products must be used with caution. Only look for the transition line. (See the jagged, golden line that marches northward from image A to image B above).

Do not even bother with this tool if it is not a mixed precipitation event. When analyzing the radar image of the sleet/snow mix on the move northward, keep in mind that the fuchsia color to the north is snow and the same color to the south of the transition line is sleet. It is the mix of precipitation types that this product shows so well. More important, when you get beyond roughly 60 miles from the radar, dual-pol is not really helpful because the radar beam samples too high above the ground. For this reason, stick to using it only for determining when the transition of precipitation types occurs: combination of rain, freezing rain, sleet and/or snow will arrive and/or exit your area of responsibility.

This transition line could be seen south of Milwaukee as early as 11 a.m. (image A; white circle). Snow began changing to sleet in Milwaukee around 3:50 p.m. The radar image at 4 p.m. indicates the transition line (image B; white circle) moving over the entire city of Milwaukee at that time. Tracking this transition line using Correlation Coefficient could have given the Milwaukee region nearly five hours notice to a change in precipitation type.

Narrowing down the timeline of a precipitation change can help considerably. In this case, it is possible to have a clearer idea of when to more effectively put down materials by monitoring the advancement of sleet into Milwaukee. In other storms, having a good timing for rain changing to snow can be a critical factor in road safety by having plows out and materials down when snow begins versus the expense of having crews sitting around for hours waiting for the rain to change over to something frozen.

Image C (on p 34) shows where there is more sleet, there is less snow accumulation. Changing those expectations can change operational decisions as well. Even with the important caveats surrounding the use of dual-pol radar products, the safety and budget benefits make it a very worthwhile tool.

Plan on it

Now is the time for planning how your department will incorporate all aspects of weather forecasting into your operational decisions. Having a plan is the cornerstone of the weather segment of the American Public Works Association’s (APWA) Winter Maintenance Certificate Program.

“When choosing what tools and services are needed to make the right decision, having a plan is critical,” said Jon Tarleton, head of transportation marketing at Vaisala and meteorologist instructor for the APWA Certificate Class. “During a winter storm situation, knowing what you need to look at, and where you will get it, ensures you are looking for the right information from a credible source.”

Critical components to such a plan should include evaluating which data resources everyone will be using before and during a snow and/or ice event. The key word here is everyone. When different decision makers are looking at different weather maps, radars, satellite images, surface data, etc., they are never really on the same page. RWIS is another important tool when considering operational decisions. However, if staff is not trained on how it will be incorporated into action or one person is looking at a private RWIS system while someone else is speaking about a locally installed system without verbally identifying what they are referring to, confusion ensues. This often happens in reference to weather forecasts as well, whether they are public or private. “Everyone on the same page” should be the motto for a truly effective plan.

Never ask a meteorologist, “What’s the weather going to do?” They will tell you all sorts of information that is not relevant. You will get frustrated and trust will be diminished. Explain your specific concerns today, before the big snows arrive. When they understand that you must make a change to 12-hour shifts at 11 a.m., they will plan to have the latest ready for you. Or if they know that dirt roads have different weather issues than paved roads, they will give you your key data points right up front. Now is the time to get all your vendors on the same page. Operations are complicated enough. A few steps of clarification today will simplify your process in areas where that is possible.

All winter maintenance road crews have requirements in common. However, there are many jurisdictional nuances to every supervisor’s actions. Keep those in mind when making your plan. Everyone involved will be grateful that your decision-making infrastructure is as dependable as the road and highway infrastructure you maintain all year round.