A snowfighter’s perspective

I work for the city of Fishers, Ind., a growing suburb just northeast of Indianapolis, as foreman of the streets department.

From 2000-2017 our community exploded, its population more than doubling. In 2000, we had 37,000 residents and 120 center-lane miles. In 2017, we had 92,000 residents, 383 center-lane miles, with 1,700 lane-miles of road to maintain. Some of our roads went from two-lane roads to as much as seven-lane roads. We grew from town to city, and maintained the same surface area of 37 sq miles during this period. We currently average adding an additional seven center-lane miles per year. We also took over winter maintenance for 21 schools, 19 parks, the city municipal complex, five additional fire stations, the downtown district, the public library and 50 miles of city-owned sidewalks and paths.

We quickly needed to change the way we did our snow removal, and here is our story.

“That’s the way we’ve always done it” was a phrase and mindset we had here for a long, long time. We had to change—not just our organization, but also our frame of mind. Buy-in is the toughest thing to get internally, but once we had it, the rest would be easy.

In 2007 we had 20 pieces of equipment for winter operations for 295 center-lane miles of pavement, and we were growing faster than we could plow. We had to hire contractors to help, which ate up a lot of our budget. Worse, who we hired were not quite maintaining the standards that we held ourselves to. So we had to go back and check all their work and fix any issues so that it met our standards. Which cost even more time and money.

Presently, we have 68 pieces of equipment available for winter maintenance and no longer use any contractors. Every vehicle we purchase must be able to move snow in some way. In 2007, we had 27 people on our winter operations staff, comprising the streets department, the mechanics and the administrative staff. Now we can have as many as 120 people available for winter operations. We split them into two 12-hour shifts. We use these same shifts year-round for snow, severe weather, storm cleanup, flooding and any other issues that arise. We hire 30-40 part-time seasonal employees each winter season and train them our way on our equipment.

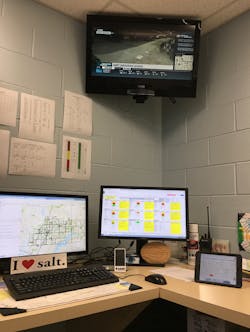

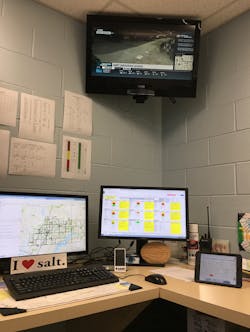

The Fishers Street Department can now track all vehicles out on the job and is able to coordinate all drivers via tablet in each vehicle.

The old way

How we used to handle winter operations was, basically, we watched the local weather, and from that made our best guess of when a weather event would start and what kind of weather we were expecting. Then we scheduled our staff. After they reported, they got in their trucks and went to the same roads in the same order as the last storm. It did not matter if we got 2 in. or 12 in. Same roads, same order. After shift we asked them how much material they used on the road, and we got their best guesses. Some estimates were pretty crazy, or so we thought. We asked the crew if they got all the roads and of course were told “yes.” But the phone calls we got from residents sometimes told a different story. We had to go out and check all these complaints and then send the drivers back to address the areas they missed. Then we tried to figure out what happened to the truck.

Time for a change

We knew we had to change but were not sure where to start. The streets department took care of plowing, but as we grew as a community the department was not growing at the same rate. We were overworked and did not have enough trucks.

We decided, as a first step, to make all city staff and trucks available for plowing: Get rid of the contractors, pay our own people and train them all to do the work up to the standards of the streets department. This resulted in the creation of a snow-fighting team. We involved our staff in the decision-making process. It is much easier to gain buy-in if each person has a voice and knows their opinions and ideas matter.

We work 12-hour shifts, but we break up our start times so that half our staff is always on the road, that way we are getting roads worked during both the morning and evening rush hours.

We also started calibrating our trucks and found that we were putting out way more salt than we thought—or needed. A 2-in. gate opening and an auger speed of 3 meant a whole lot of different things from truck to truck. We did not exactly calibrate them, but we knew what was coming out of them at all auger speeds and gate settings. We had 12 trucks with 10 different controllers at the time. We laminated these settings for each truck and told the drivers how many pounds per lane mile, and they set the gate and auger accordingly. At the start of each shift each driver was given a tracking sheet to track mileage, salt, brine, hours, coverage area, shift time and date of operations.

Then we divided Fishers into seven “areas.” Areas 1, 3, 5 and 7 start a 9 a.m./p.m., and areas 2, 4 and 6 start at 10 a.m./p.m. We created maps for each area designating primary and secondary corridors, subdivision roads and cul-de-sacs. Each area had a leader, and it was his job to make sure all the streets in his area were plowed. But we still missed some streets and still had the old habits of starting at the same place every time, so we then broke each area into four quadrants and started in a different quadrant every storm, which cut down on the complaints of “when will you plow my road?”

As for “What happened to the truck?” we introduced vehicle inspection sheets for pre- and post-shift, which compiled a rundown of items concerning the engine compartment, the exterior and everything in the cab, all of which had to be inspected and checked correctly.

Then we started to experiment with liquid deicers. We got a tank and pump and bought brine from a neighboring public works department. We quickly saw the benefit of adding brine to our arsenal; we also realized we would do much better if we made our own. So we bought a brine maker, a trash pump, some hoses and a storage tank. This quickly paid for itself. We added a tank for CaCl, and this expanded our abilities even more with the periodic deep-freezes we endure. We pre-treat when we can, but we get a lot of mixed precipitation during the winter.

The city was divided into seven areas for snow and ice operations management.

How we do it now

We are adding wing plows to our tandems, increasing our ability to clear roads faster. When we purchase a new truck, it is from a specific bid sheet that has a pre-wet system and is equipped with a spreader controller, which makes life much easier for calibrating and for our operators.

We also have embraced technology. This was a particular challenge, since most of our staff were not tech-savvy. We now have iPads for all our trucks. These iPads contain color-coded area maps, material tracking sheets, vehicle inspection sheets, and, most importantly, area assignments and storm instructions. These are all living documents tied into spreadsheets in our database. These spreadsheets also fill out invoices, so that we can immediately bill the places we charge for snow-removal services (e.g., the schools, library and downtown district). Drivers can open their snow assignments and see what truck they are in, what area they are covering, who else is in that area and what their instructions are for the storm. Instead of trying to communicate with up to 60 drivers by radio, I can type out a driver’s instructions and just relay over the radio: “When you have a chance, pull over and check your iPad.” No more confusion or repeating instructions a dozen times. We changed from our old standard operating procedures to treating each individual storm as a unique event. We also went to vehicle-tracking hardware. We can see where all our trucks have been and when they were there. No more missed roads.

And perhaps the most important change we made is that we stopped relying on the nightly news for our weather information. We now source from multiple weather services, accumulating all this data together, and deciding how to staff and treat the event accordingly. We always strive for bare pavement on all our primary and secondary roads. We also are quick to change how we attack an event as the storm changes.

We have access to Fishers’ traffic cams, so we can see the conditions of our major intersections, as well as current traffic patterns. We have a mobile weather sensor that we can mount on any vehicle, which gives road temperatures, identifies water or ice film, freezing point, air temperature, friction and dew point every 15 seconds, and maps all this out as the vehicle drives.

What’s next?

Trust me we are not perfect and not everything we tried worked. In our efforts to improve our operations, we have had failures. It is what you do next that defines you. We are not afraid of change anymore, and we will continue to do our research and try new things to improve our ability to keep up with our growing community and its needs.