State of the Bridges: Call it progress?

The state of Rhode Island likes the potential of the crane.

Today, the equipment is being used to build or repair some of its structurally deficient bridges, which comprise 25% of Rhode Island’s bridge inventory. A few years from now, however, the lifts could signal an economic boom.

About a year ago, lawmakers passed a 10-year, $4.7 billion plan to fix spans across the state, which ranks dead last in the U.S. in terms of bridge condition.

“[The program] was meant to get our roads and bridges in a state of good repair with a focus primarily on bridges and job creation,” Peter Alviti, director of the Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT), told Roads & Bridges, “[Not] just the jobs that come with the reconstruction and renewal of our transportation infrastructure, but to [also] design the jobs and projects in a way that created a transportation system that encouraged additional economic development. So once the cranes of reconstruction of the infrastructure leave, the cranes of new businesses can begin.”

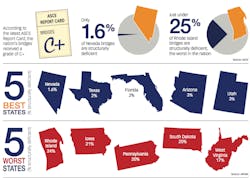

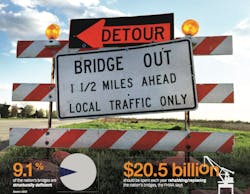

Cranes continue to dominate the U.S. landscape, as many states have turned to credible and expensive bridge reconstruction programs in an attempt to improve their crossings. The movement, however, has thus far created just a flicker of improvement. According to the latest ASCE Report Card, 1 out of every 11 bridges in the U.S. is structurally deficient; in 2013, it was 1 in 9 (9.1%). ASCE looks at the following when rating bridges: capacity, condition, funding, the cost to improve a bridge and the funding to address the need, operations and maintenance performed on the bridge, public safety, resilience, a bridge’s capacity to prevent hazards, whether it’s man-made or natural, innovation, and ways of preserving a bridge that can be utilized to save it. ASCE recently gave the nation’s bridge system the same grade it got four years ago: C+.

What is cramping the progress is what ASCE’s Andrew Herrmann calls “the bubble moving forward.” There is a large sum of spans out there that were built in the 1950s and 1960s and are now past their design life.

“Bridge engineers are getting nervous about it,” Herrmann told Roads & Bridges. “The scary thing is 39% of the bridges out there are 50 years or older. That is the bubble I am talking about. It is like a debt that is coming due.”

To avoid continued public confusion, and also to meet the performance-based demands of MAP-21, the FHWA now classifies bridges as good, fair or poor. Functionally obsolete bridges are now, well, obsolete as far as numbers go. Funding at the federal level remains relatively flat, and the Trump Administration is looking at replacing the TIGER grant program, which helped many states address bridge maintenance issues. Currently there is a $123 billion backlog of bridge needs in the U.S. and 188 million trips are taken across structurally deficient bridges every day.

“We have these older bridges that we historically have not been maintaining as well as we should have,” according to Herrmann, citing an FHWA report in 2013 that revealed the U.S. should be spending a total of $20.5 billion a year on bridges; only $12.8 billion was being used. “We haven’t been making the investments.”

Turning behavior around

Rhode Island is one of several states which has been trying. Before Gov. Gina Raimondo took office, RIDOT was like a tweener hunkering down for summer break. Very little was getting done on the home front, and the lack of activity was costing money. The agency was not designing, but instead paying consultants to draw up plans. RIDOT would make some changes, then send them back to consultants for revisions. In terms of funding, 80% of Rhode Island’s comes from Washington, with the state making up the remaining 20%. However, during RIDOT’s adminstrative laziness, debt was accumulating to make up the state’s portion. Money coming from the gas tax and registration fees, which should have been pouring into the DOT coffer, was instead being diverted for other needs.

“Before they had a four-year plan that was never fully funded, so the same projects would get regurgitated every four years,” said Alviti. “Some would get done, but many would not.”

A black-eyed example of RIDOT’s incompetance was the Rte. 6/10 interchange project, which sat in the design phase for over 30 years.

Now the gas tax and registration fees are feeding the agency and soft costs (the consulting fees, legal costs, etc., which would amount to 40-50% of the total project cost) have been virtually eliminated. RIDOT has become much more efficient with its project delivery (design-build, design-build-operate-maintain, public-private partnerships), and the debt is getting defeased. RIDOT did add $300 million of additional GARVEE bond debt, but at the same time refinanced the troubling debt at a 2% interest rate.

Still, Rhode Island’s 10-year Road Works plan was 10% short of its funding goal. The state turned to tolling trucks at 14 structurally deficient bridges. All the money will be used to repair or replace those unhealthy spans, and once that task is complete tolls will stay in place for the purpose of funding other transportation-related projects.

So far the Road Works program has been a huge success. In 2015, RIDOT executed $170 million of project support, which was $70 million more than in 2014. This year the agency is working with a $213 million project budget, and the Rte. 6/10 interchange will finally get the attention it deserves. The $400 million job will be in full swing this year. FAST Act dollars also are factoring into the revival. Last year RIDOT had a $10 million increase in federal funding (a total of $220 million) and in 2017 the figure is $225 million.

RIDOT’s new approach is to mix in bridge rehabs with complete rebuilds.

“It’s based on an asset management approach, which we hadn’t employed prior to this,” said Alviti.

Getting out in front of the problem will cost RIDOT 10% less than traditional methods.

One bridge on its last leg was located in East Providence. Carrying Rte. 114 over Warren Avenues, the structure was literally being held up by timber reinforcement. RIDOT executed accelerated bridge construction and slid two new decks in place over a weekend.

Tending to those in need

Iowa ranks in the bottom five in terms of the overall condition of its bridge inventory. However, the Iowa DOT is up on what needs to be done, and has been executing an aggressive plan to near perfection. About a decade ago there were over 250 structurally deficient bridges in the state. Now there are about 60. Help from the Iowa legislature has accelerated the transformation. Senate Bill 257 increased the state gas tax by 10 cents a gallon, and for the primary routes that amounts to about $100 million more a year. In 2015, Iowa spent $157 million on bridges. A year later it was $254 million and in 2017 it will be $188 million. FAST Act money also is mobilizing the effort. Iowa is receiving about $60 million more in federal funding per year.

But unlike Rhode Island, the energy is being focused mostly on the weak.

“We have a lot of work out there to do so it is harder to be in preventive mode right now,” Scott Neubauer, Iowa DOT bridge maintenance and inspection engineer, told Roads & Bridges. “We have bridges that need work because they are starting to deteriorate. It’s hard to get to [the preventive] point when you have problems out there that need to be addressed.”

One of those problem bridges is the I-74 bridge over the Mississippi River. A joint venture with the state of Illinois, the $450 million basket-handled steel arch bridge project will increase lane capacity from four lanes to six.

“We have a wave of bridges coming at us here that were built in the 1960s and 70s that are getting towards the end of their life,” said Neubauer.

Comfortable where they are at

Iowa’s neighbor to the north, South Dakota, has an identical yard. State-owned bridges are in good shape (over 95% are in either good or fair condition), but the struggle continues at the local level. The state legislature enacted the Big Improvement Grant, which created $10 million for bridge repair.

“We are pretty comfortable with the dollars we are spending on the state bridge system,” Steve Johnson, chief bridge engineer with the South Dakota DOT, told Roads & Bridges. “We think at least in the near future we can maintain the condition of state bridges about where they are at or maybe slightly improve them.”

One state-owned structurally deficient bridge is about to feel new again. Exit 14 on the I-90 interchange in Spearfish is expected to be completed this summer, and also will help congestion and accommodate pedestrians.

Designs are underway to replace a bridge over the Missouri River that connects Pierre with North Pierre. It is presently a non-redundant steel girder bridge that has experienced fatigue cracking. The replacement will be a four-lane steel girder bridge.