What will it take?

Vision Zero is a movement based on the Safe Systems approach to road safety, which is centered on the idea that “no loss of life is acceptable on our streets and roadways.”

Originating in Sweden in 1997, that country’s incorporation of the Vision Zero framework into roadway planning and engineering practices has been accompanied by an impressive decline in traffic fatalities, even while traffic volumes have increased; other Vision Zero adopters, such as the Netherlands, have also seen similar declines in traffic fatalities over time.

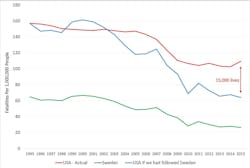

During this same time period, traffic safety improvements also have occurred in the U.S.—but they pale in comparison to improvements in Sweden (see Figure 1). In the U.S., tens of thousands of people—children, parents, friends, neighbors and co-workers—are killed in collisions with motor vehicles every year. If the U.S. had followed Sweden’s trend, nearly 15,000 lives would have been saved in 2015 alone. Fifteen thousand. We can and must do better.

It is in this context—an awakening to the fact that our “normal” does not have to be so—that Vision Zero in the U.S. has caught fire. State and local Vision Zero efforts have taken the state and federal initiatives of Toward Zero Deaths and Road to Zero, respectively, even further to reorient our everyday practices toward a bold safety objective. Vision Zero has a few fundamental tenets, explored in more detail elsewhere, but the most important to reiterate here is the idea that humans can and will make mistakes, but the system should not fail. A direct derivation from this tenet, therefore, is that our transportation system should be designed for a speed that fosters human life and health. This does not mean that we never again build highways, but it does mean that we are sensitive to context and that we incorporate separation in time and space so that all road users—whether walking, bicycling, riding a motorcycle or driving—can safely make it to their destination without unnecessary hardship.

This recognition also does not mean that education and enforcement are not important parts of the solution. Rather, reaching “zero” will necessitate a multi-pronged, systems-level approach that recognizes where education and enforcement can influence individual behavior and where systemic influences, such as those reflected in the built environment, are more powerful tools.

With these principles in mind, this article explores the potential for Vision Zero in the U.S. Let us make no mistake: grand changes, including sweeping cultural changes, will be needed to approach the goal of zero roadway fatalities. But as we explore further here, experience suggests that the Safe Systems/Vision Zero approach could yield dramatic traffic-safety improvements in the U.S. Strong leadership, data-driven solutions, performance measurement and a focus on equity have proven to be critical success factors in U.S. cities that have set out to match the Vision Zero successes already experienced in European cities and countries.

Leadership

When looking at Vision Zero efforts that have borne fruit in the U.S. and globally, a common and important first element includes a committed team and leadership support. While “safety” is a stated goal of virtually all transportation agencies, the reality is that it has too often been subjugated to the demands of mobility, and changing this paradigm will require strong leadership to help steer the effort through inevitable rocky patches. Thus far, the Vision Zero cities that have seen the most results are those in which the mayor, city council and public agency leaders have declared their support and followed their words with resources in the form of data-driven investment in improvements, programs and staff time.

This multi-pronged leadership approach is not only critical for creating and establishing momentum, it also acknowledges the overlapping responsibilities of, for example, public works, planning and emergency services in working to achieve Vision Zero. When people share responsibility for the outcomes, they are more likely to work together to achieve them. This not only lightens the load on any one agency, it strengthens the mission across agencies and fosters collaboration with regard to budgeting and resources. For example, the departments of transportation, public works and law enforcement worked together in Los Angeles to get approval for a joint Vision Zero budget in 2015. In Seattle, the departments of transportation and law enforcement share data to allow for data-driven enforcement, leading to a more efficient and equitable use of resources.

Data-driven analysis

Critically, we cannot hope to reach zero deaths if we do not understand why crashes are occurring and what could be done to prevent them. Thus, a second important aspect of Vision Zero is to let the data lead you, and to utilize various types of data to inform your understanding. The primary quantitative data that inform Vision Zero strategies are crash-related data, which offer the opportunity to assess traffic-safety issues in a transparent and, ideally, unbiased way. There are multiple methods of examining crash data, whether through collision-trend analysis, hotspot examination, crash-rate comparison, the development of a High Injury Network and/or a more systemic safety analysis. All of these methods can reveal helpful insights about who is getting injured, how and where, and these insights in turn should guide future actions and efforts—particularly with regard to serious injuries and fatalities. Importantly, Vision Zero efforts need to employ some type of systemic analysis—i.e., some way of screening the network to understand patterns in where crashes are occurring rather than just where the crashes occur—to be able to identify and prioritize locations for pretreatment that are likely to experience future crashes. A goal to reach zero means moving from reactive to proactive strategies and prioritizing treatment for the most injurious crashes.

The New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) recently completed a study on left-turning crashes that illustrates this point well. After reviewing multiple years of pedestrian and bicyclist crash data, left-turning crashes were identified as particularly injurious—and found to occur at just 18% of city intersections. Further analysis revealed a particular association with one-way streets and certain elements of driver behavior influenced by other aspects of the street design and context. Using these findings, the NYCDOT employed a set of targeted countermeasures at a sample of locations throughout the network and measured their effect on injuries over time, finding a decrease in pedestrian and bicyclist injuries ranging from 14% to 41%, and a better-than 50% decrease in pedestrian and bicyclist severe injuries and fatalities for some treatments.

One needs the right data to do systemic safety analysis well, including an understanding of roadway design features and driver, pedestrian and bicyclist exposure. While many cities and counties are far from having this detailed exposure information, building a database of multimodal counts and supporting roadway design, land use and context information can enable the creation of models to estimate network exposure. Additionally, research has shown some promise in using crowd-sourced data to estimate exposure; undoubtedly, this potential will only improve as data and connectivity become more ubiquitous.

In addition to quantitative data, qualitative data is critically important for understanding safety issues that may not be captured in crash data. While data such as those gathered through Vision Zero surveys or crowd-sourced applications can be helpful, it is important to evaluate who is represented in that data and conduct targeted outreach to underrepresented groups as necessary to achieve balanced coverage and feedback.

Figure 1. Traffic fatalities per 1 million people in the U.S. and Sweden, from 1995-2015.

Performance measurement

Related to data, a third important aspect of Vision Zero is to measure performance so that agency staff, advocates and the public can be engaged with and monitor Vision Zero progress. Performance measures can be either outputs or outcomes—outputs are generally easier to measure, but outcomes are those in which we are ultimately most interested. Additionally, measures can range in breadth and detail depending on the context, but the general idea is to work toward a balance of flexibility and accountability—flexibility to alter strategies if the data or feedback indicate a different approach is needed, but enough accountability that ensures that the public can see and understand the progress toward the goals.

Ultimately, monitoring performance helps practitioners and the public to see and celebrate successes. For example, after efforts to curtail speeding in Washington, D.C., staff observed a drop from 33% of motorists driving over the speed limit to just 2.5% of drivers doing so—accompanied by a reported 70% reduction in fatalities in the evaluated locations. When the goals are not being met, these same measures can help practitioners and leaders adjust course as needed.

Sensitivity to equity

A fourth important aspect of any Vision Zero effort is the prioritization of equity. Elevating equity as a value helps ensure that historical inequities do not continue under Vision Zero, such as tendencies for transportation resources to be disproportionately invested and outcomes to be disproportionately impactful, both according to mode and segments of a community. For example, many Vision Zero cities have found that their High Injury Networks heavily overlap with areas often labeled “Communities of Concern,” a label that is defined differently depending on the jurisdiction, but tends to correspond with areas of the community with higher-than-average concentrations of people of color, children, elderly and/or zero-vehicle households.

Another aspect of equity is the need for our solutions to be data-driven, particularly by being responsive to community input, which often comes in qualitative forms. This is particularly important with regard to enforcement, which can be a critical part of a Vision Zero effort, but not if increased police presence heightens other community tensions. Engaging the parts of the community feeling the brunt of certain traffic-safety issues is critical to their buy-in and, ultimately, to success. A great example of this can be seen in how the city of Portland, Ore., worked with the community organization APANO while responding to multiple pedestrian fatalities along that city’s SE Division Street. By closely coordinating with the parts of the community most directly impacted by the traffic-safety issues, the city was able to ensure solutions that worked for the community and larger traffic-safety goals.

Stamina and creativity

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that Vision Zero is no small undertaking. In addition to strong leadership and commitment, it will require creativity and a diverse suite of tools, as well as the stamina to withstand inevitable challenges and overcome stubborn norms. In this regard, it will be important to draw from the many resources available to support Vision Zero, including resources on Systemic Safety Analysis, design guidance to create safer conditions for all roadway users (e.g., FHWA’s Achieving Multimodal Networks), resources from the Vision Zero Network and an upcoming ITE Vision Zero Toolbox.

It also is critical to learn from those who have gone before you. Although every Vision Zero effort will be somewhat unique, it can be helpful to review others’ efforts, see what they learned after initial work, and use that information to tailor your approach. The Vision Zero Network has published multiple case studies (http://visionzeronetwork.org/resources/case-studies/) on various aspects of Vision Zero, as well as example plans, progress reports and other documents that can serve as valuable references for developing a Vision Zero Action Plan and putting it into practice.

If the challenge still seems too great, consider that even Sweden has had its ups and downs. Yet, traffic safety under Vision Zero is clearly far more robust today than in 1997. We may never reach “zero,” but committing to safety as our top priority and incorporating a Vision Zero/Safe Systems approach gives us the potential to create a future in which traffic fatalities in our communities are a rare, rather than routine, occurrence—a worthy goal, indeed.

The author would like to recognize the contribution of multiple Vision Zero cities and the Vision Zero Network in providing resources for this article.