Web Exclusive: Thinking like a meteorologist

If you have ever built anything, you have probably heard the old saying, “Measure twice, cut once.”

The first time you did not follow it, you quickly learned the lesson. Making an accurate measurement is important, otherwise you end up wasting time. If you think of weather, have you ever wondered why television meteorologists tell you the current temperature at the airport, rather than the temperature downtown? Or if you manage or perform snow-removal operations for your agency, have you ever used an infrared “temperature gun” thermometer, perhaps held out the window of your truck? If so, have you ever questioned the accuracy of its results? These questions address one of the most important parts of understanding the weather—knowing how to measure it.

Maybe it is because a weather forecast is not always perfect, but for some reason we treat measuring weather in winter road maintenance in the same sloppy way. The weather can be very complicated at times, but knowing what is going on right now is simple. If you do it correctly, you can improve your winter decision-making, increase efficiency in your snow and ice operations and make life during a snowstorm a little less stressful. When you think of how and where to get the information on “now,” you need to think like a meteorologist, and remember that accuracy and dependability are key. Let’s talk about how to properly measure weather parameters such as temperature, wind direction and road condition.

An example of a nonintrusive laser sensor for recording temperature.

The right temp

So why do TV meteorologists tell us the temperature at the airport and not someplace else? After all, nobody lives at the airport, right? They do it because meteorologists around the world know that the temperature taken at an airport was measured correctly.

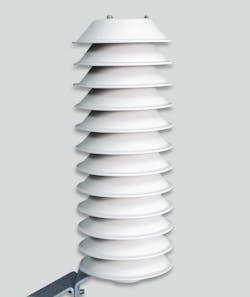

All airports and professional weather stations measure air temperature at 6 ft off the ground surface in a white enclosure. Why do they do this? Six feet is still at a height where we walk around on this earth, yet high enough above the ground to avoid excessive radiative influence from its surface. The sensor is housed in a white enclosure to avoid influence from the sun’s rays. (Bear in mind that ultraviolet rays reach the Earth’s surface even on cloudy days.) In addition, the station is in a grass clearing typically in the middle of the airfield, a situation that assures consistency. Any variance in a station will affect the station’s readings, which means we cannot compare one location to another. The location of the air temperature sensor is not where you plow snow, of course, but it can tell us the type of precipitation that is falling or is going to fall.

Weather forecasts are not perfect, we all know that. When they are less than wholly accurate, we are usually complaining about rain or snow falling that was not predicted—but I bet you were never upset that the meteorologist got the wind direction wrong. More than likely you never even noticed if it was right or wrong, yet the wind direction is a crucial factor in a weather forecast (even if it seems only a meteorologist cares about it).

As a storm approaches, typically it is part of a large surface low-pressure system with a counterclockwise wind flow around the storm. If your winds are blowing from the northeast it means the center of the low is passing to your south, which would put your agency in a location for snow. If winds are blowing from the south, then the center of the low is passing to your north, and you will likely receive rain followed briefly by snow as it ends. If your winds are blowing from the northwest, it means the storm has already passed either to your north or south, and colder, drier air is filtering in, which will limit or even stop any additional snowfall. So, noticing and understanding the impact of the wind direction can mean a lot. If the wind direction does not match your forecast, then maybe the low has shifted, and your forecast is off well before you receive an update. Winds are a great early predictor of the location of a storm center, and thus key to helping any winter snow-and-ice operations worker make decisions.

The big question

As a storm moves overhead, the big question usually is, “Will it stick?”

As already discussed, air temperature is effective in determining the type of precipitation, but unfortunately is little help in determining if that precipitation will freeze to your road surface. The main reason is that what is being measured is the air and not the concrete or asphalt surface. They both behave very differently as to how they gain and lose heat. In fact, differences of as much as 10-40°F are common. Therefore, it behooves us to stop using air temperature to make maintenance decisions, but rather to look to pavement temperature when using road chemicals, because that is how their effectiveness is measured.

What are the measurement choices? Some of us might think our eyes are a good choice. They tend not to let us down; however, they are not good at all at seeing differences in temperature, unless there are clear signs present, such as fire or smoke. Plus, we cannot visually determine how the temperature is changing. Therefore, we must measure the temperature of the pavement to make an informed decision.

To measure the road surface, we have two choices. We can place a thermometer directly into the surface of the pavement, or we can use infrared technology to measure it from above or from the side. Embedded sensors work extremely well, and are very accurate at providing this information, so when the pavement is just above or just below 32°F, we can make very accurate decisions. These sensors also are used to make pavement forecasts that allow DOTs to plan for the impact the next storm will have, and when precisely it will arrive, or whether temperatures will cool enough to cause problems. Sensors that mount to the outside of a vehicle and report information into the cab or over the Internet also are a good choice; they offer flexibility and a resourceful return on investment. They are not, however, a solution for advance warning—which ties back into the necessity of first having an accurate reading of the air temperature.

An air temp sensor, similar to those used at airports, housed in a white enclosure.

Not so fast

A very popular method, and one I alluded to at the beginning of this article, is the use of infrared “temperature guns.” These devices seem like a great idea. They are mobile, easily operated and require minimal expertise to interpret. They also are very inexpensive, but that is where their value ends. An infrared device must know the temperature of the air in the environment being measured, so in other words, the sensor must be acclimated to the air temperature to tell the temperature of the road. Well, think of how most people use the gun. It sits in their warm vehicle and then is brought outside or stuck out the window only when needed, so it never has a chance to reach the outside air temperature. These guns were designed to measure industrial objects at high temperatures, when it is easiest for an infrared device to measure temperature. At cold and subzero street temperatures, very little infrared energy is leaving the road surface and thus able to be detected. And so again, an accurate device specifically designed for winter operations is needed. In this regard, a void exists. It is not my recommendation that an agency should throw away their temperature guns, but rather to remember that when employing them in cases when the road is hovering around 32°F, the surface could be several degrees on either side of freezing.

Once a storm is overhead and you are in full operations, the need for road weather data shifts towards the road condition, or how the road is behaving in the storm. Sure, temperatures (air and pavement), winds, precipitation and timing are still extremely important to someone able to look at the big picture, but for the “in the trenches” operations, things need to get really simple. What you need is a numeric value for the road condition. That value is the grip of the road, or road friction. Newer, non-intrusive sensors that use lasers can measure the road surface from the side of the road and report this grip value. By using a sensor such as this, you can objectively look at readings from around your network and determine how your operations are changing the conditions.

For winter maintenance operations, you should always begin your decision-making with a quality forecast from a trusted source, such as a private service or a National Weather Service office. A forecast helps with planning storms days and event hours away. Once the storm is upon us, while a forecast is always important, your needs should shift towards getting reliable information on what is happening now, and if the forecast is turning out as planned. If your information is not coming by a sound method using sound instruments, you will be making bad decisions, or at the very least, having to revise your decisions several times, which will cost you in time, resources and materials. By following these suggestions, you will keep your stress level at a more manageable level, and it will ensure everyone—community and crew members alike—has the best chance to get home safely.